|

LIFE AT HASELOR VICARAGE |

|||

| By Lt Colonel William Sykes | |||

| (William Sykes, son of Rev. John Heath Sykes, Vicar of Haselor 1867-1912) | |||

| This fascinating account of Life at Haselor Vicarage in the 19th century, was only known locally in 2007. A chance meeting with Martyn Davey (Churchwarden) in Haselor Church by William Sykes, who said that his grandfather had written about life at Haselor vicarage. | |||

| To make it more interesting, I have added pictures with names to correspond with the story. | |||

|

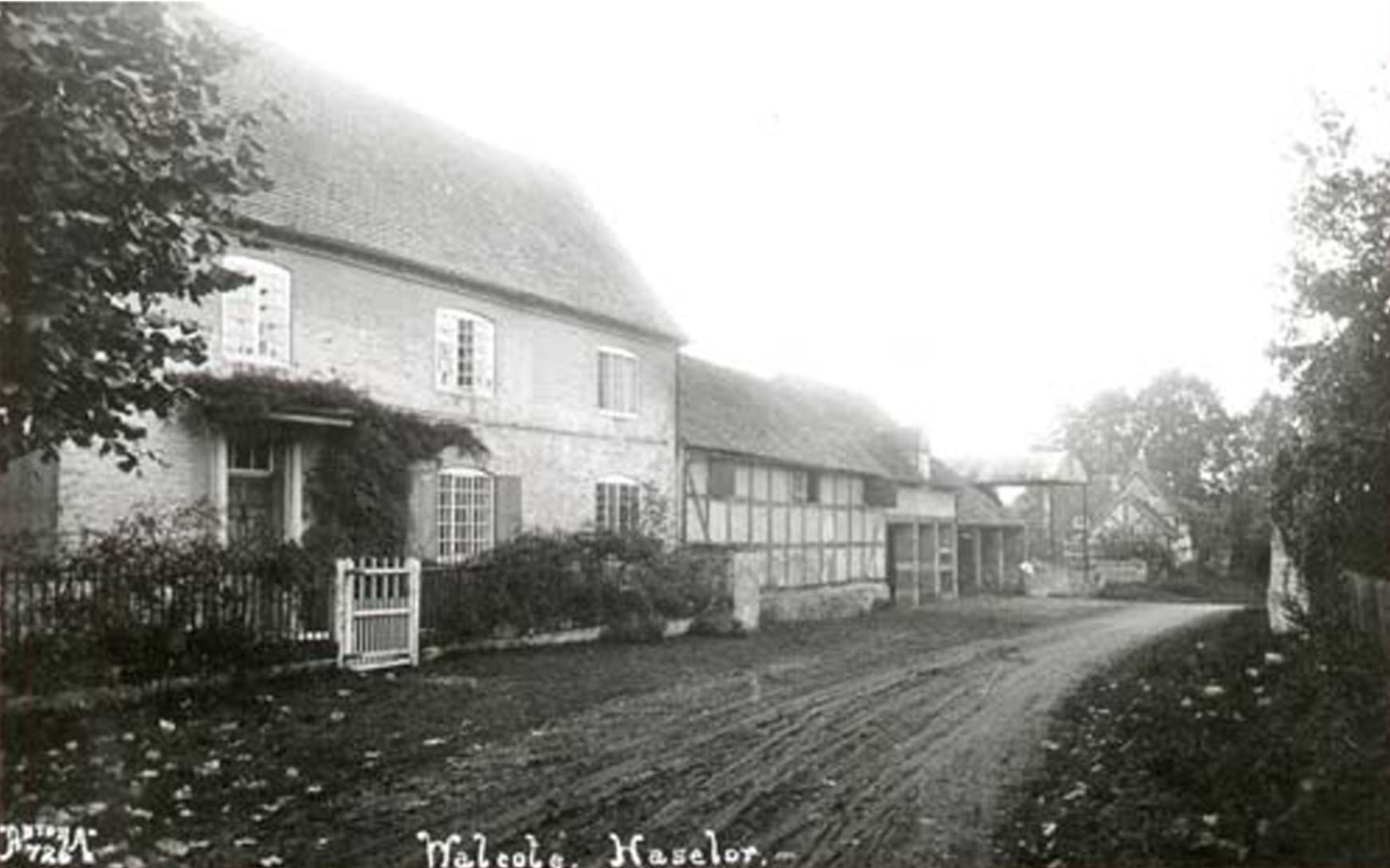

John Finnemore, Walcote Farm |

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

In these days of shifting values, superficial security, scientific inventions, of noise and speed and mass production, it is sometimes a relief to turn back to the experiences of a childhood, not without its hardships, but lived in a more leisurely, less complicated world. Memory often draws a veil over the harsh and unhappy things. and blunts the edges of childhood’s sufferings, so that, re-living those vicissitudes, excitements and matters of absorbing interest consisted in and were created by the simple realities of a life lived in the heart of the Warwickshire countryside.

|

|||

|

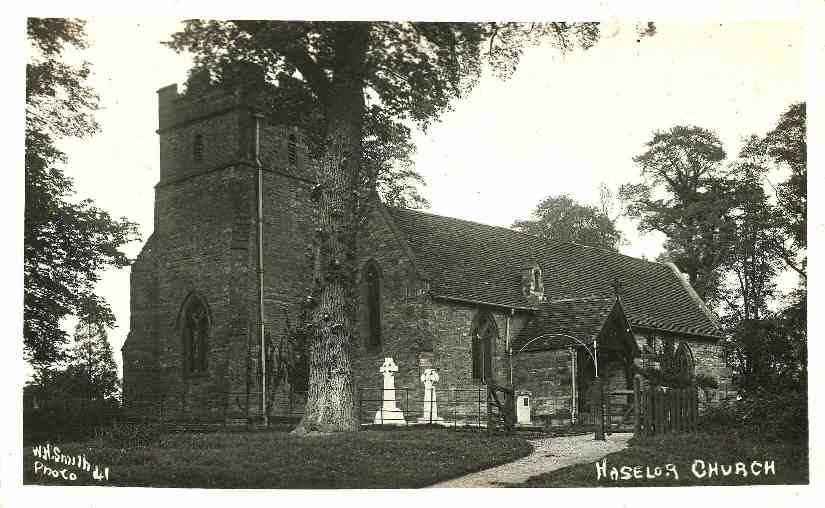

In those days the Vicarage was the centre of village life in Haselor. The house, not old as houses go, for my Father had it built, yet has a certain mellowness in its warm red brick which gives an impression of age, as it stands today, pleasantly modernised and dreaming in the spring sunshine. The rooks still build in the elms nearby. Across the lane and up the steep incline the little church stands, gathering around it, on weathered, crooked tombstones, the names of many who were the life and essence of the village community into which, in 1867 I was born. I was the fourth arrival in a family which, year by year, with almost clockwork regularity increased until it reached a living total of fourteen - six girls and eight boys.

|

|||

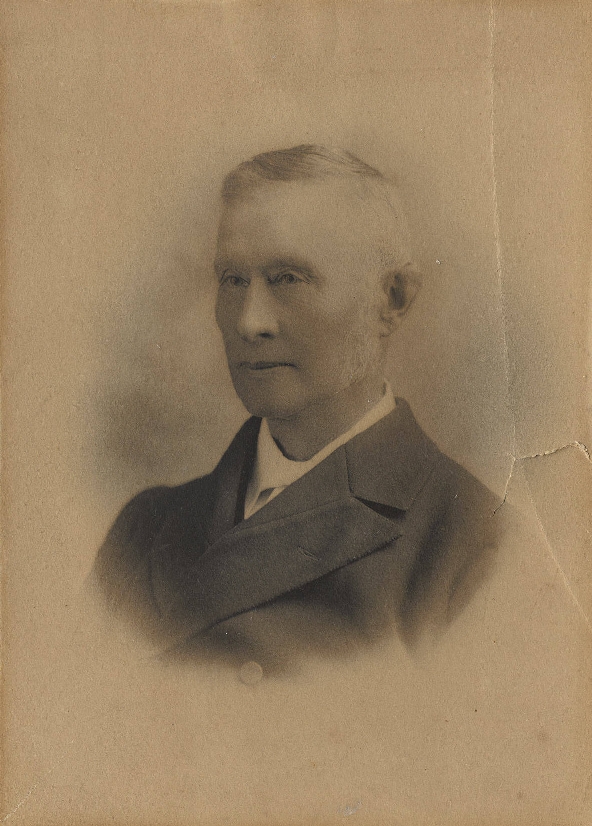

| Reverend. John Heath Sykes | |||

| Information supplied by Sir John Sykes Bt. Great grandson of Rev. John Heath Sykes and grandson to Francis (Frank) William Sykes. | |||

|

I have my great-grandmother's bible which has (inter alia) the following information: "John Heath Sykes, and Frances Amelia Nind, were married, Tuesday, Augst 12th 1862, at Woodcote Church, by the Rev. William Sykes" "Francis William Sykes, born May 21st 1864 at Bishopton Warwickshire, baptized at Woodcote Church by Rev P.H.Nind August 7th1864. Sponsors. Mr Sykes. Mrs Sykes. Sir Francis Sykes"

Rev William Sykes was JHS's father, Rev Nind was FAN's father (Vicar of Stoke-cum-Woodcote, Oxfordshire) - and if one adds in JHS's elder brother, Rev Edward John Sykes, there was no lack of vicars in the family!

All 14 children's details are listed in the bible - they all had different sponsors (or Godparents) which must have been quite a task - 42 in all. The 5th child Frederick was born at Bishopton on 28th September 1868. The first to be born at Haselor Vicarage (and baptised in Haselor Church) was the 6th child, Catherine, on 26th April 1870. So it sounds as though Haselor Vicarage was not completed until the end of 1868 at the earliest, probably 1869. |

|||

|

Frances Emily 25 May 1863 (died 1955) Francis William 21 May 1864 (died Maryborough, Queensland 14 Mar 1945) John Heath 23 Apr 1866 (died Bombay 1 Mar 1892) William 27 Sep 1867 (died 3 Mar 1950) Frederick 28 Sep 1868 (died 1946) Catherine Mary 26 Apr 1870 (died 8 Mar 1956) Agnes 25 Jun 1871 (died 26 Jul 1954) Alfred 6 Jul 1872 (died 2 Jul 1954) Alice Heath 30 Oct 1873 (died 31 Oct 1959) Hugh Percival 10 Jun 1875 (died Oct 1896) Edward Ernest 24 Sep 1876 (died Mar 1950) Charles Henry 16 Nov 1877 (died Tewkesbury, Glos 8 May 1974) Mary Seymour 14 May 1879 (died 22 Jun 1957) Margaret 30 Jul 1880 (died 9 Sep 1958)

|

|||

|

John was an apprentice merchant navy officer, first on the Blackadder ( I have what is possibly his drawing of this) then on the Cutty Sark for three voyages from 1882-1885. He died from fever after shooting duck in the marshes outside Bombay. Mary (Molly) was the only one to marry a vicar. Charles, who I knew quite well, was a Captain in the Royal Fusiliers in WWI and was awarded the DSO after the Second Battle of Ypres where he was severely wounded (although this did not stop him living until 96!).

|

|||

|

|||

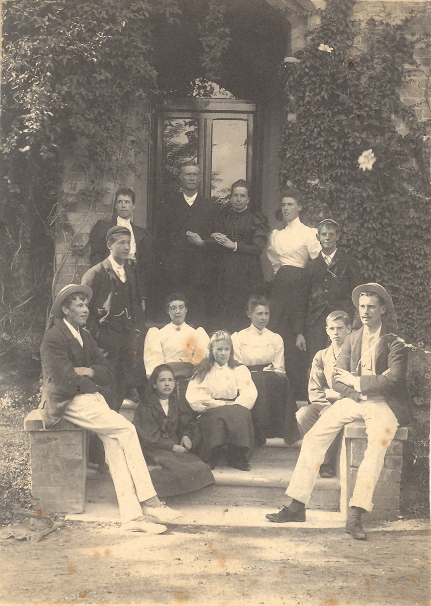

| Reverend John Heath Sykes with his wife Frances Amelia nee Nind and 11 of their 14 children outside the front door of Haselor Vicarage in Walcote c1893 Picture supplied by Sir John Sykes Bt. | |||

|

It has been a constant source of wonder to me that my mother, so small and trim and full of parochial and social activities could ever have found time for such a large family. She and my father were, in a sense, so preoccupied with each other, that we, the older ones - apart from the care of two nurses and a chain of governesses who made little impression either as personalities or teachers - were left, in our leisure hours, more or less to our own devices. As a result we mingled much with the villagers so that we knew and were known by everyone in the parish. Some of them were rare characters whose sayings and philosophies made indelible impressions on our growing minds, and were woven into our lives as strongly as the varied personalities of our own brothers and sisters.

|

|||

|

Although for years there were always babies in the family, making the usual demands common to their kind, the greatest interests for myself lay beyond the nursery and schoolroom, in the village and surrounding countryside where human-kind and wild life held for me a world of boundless fascination.

|

|||

|

The house stood on rising ground above a circular drive and from the flowerbeds around the ground floor windows, grass banks sloped gently to the gravel. It was in those banks that I deposited my first pennies in a mistaken idea that, like grown ups, I too ‘put my money in the Bank’. Alas! This early trait was no foreshadowing of the future, as my capital has never had much chance to accumulate in the less accommodating banks of the world.

|

|||

|

Beyond the grounds of the Vicarage was a small but highly satisfactory river. Often in the small hours, before it was light, I would steal out barefooted from the sleeping house, with my fishing tackle. Delicious was the shock of the long grass, wet with dew or the night’s rain, on my bare legs, and as I threw out the line I could hardly see the float against the dark water. Often my bait was an ordinary house-fly with which I would dab for dace, and sometimes I took home quite a fair catch of chub and roach, and occasionally, with all the offhandedness of secret pride, a small trout.

|

|||

|

|||

| The wooden foot bridge on right of picture, crossing the River Alne. | |||

|

I can see my father now, tall and full of vitality, striding across the fields to the same river, with a goodly following of his offspring in varying degrees of reluctance or enthusiasm, as he made for the deep pool below the wooden bridge. Here, on the bank under a large coloured umbrella, he would undress, punctuating this operation with shouts to us to hurry up and strip before he took a header into the deepest water. Suiting the action to his words he would dive in boldly, disappearing as though he had never been. As he emerged, vigorously treading water, he would call us each by name to follow suit, assuring us that it was delightful. But experience informed us differently, the current was strong, the river deep, and by the time we had plunged, felt the relentless waters closing over us, heard the alarming drumming in our ears, and swallowed great unwelcome gulps of the all pervading element, we would find, in the miracle of returning to the surface, that he was secure and triumphant on the bank, thus shaking our consistent but false hope that he would be alongside us in the water as we pushed our way to the surface.

|

|||

|

Once one of my small sisters, Agnes, who had been included in the bathing party, all too obviously against her will, astonished us greatly by refusing point black to obey the order to jump in. Instead, she could be seen, and heard, running, naked as God made her, round and round the meadow, screaming in frenzied protest. But ultimately, and in the way described, we all learnt to swim, after which, in the warm weather we would bathe voluntarily two or three times a day. My eldest brother, Frank, developed into such an enthusiast that he bathed every day throughout the year. Only once did I become infected with the same zeal, and on a wintry morning took a header without realising that there was a thin coating of ice on the surface. The physical shock was one of the greatest I had ever experienced, and as I struggled to the bank, gasping for breath, I solemnly vowed never to make such a mistake again - a promise which I have kept all my life.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Hoo Mill |

|||

|

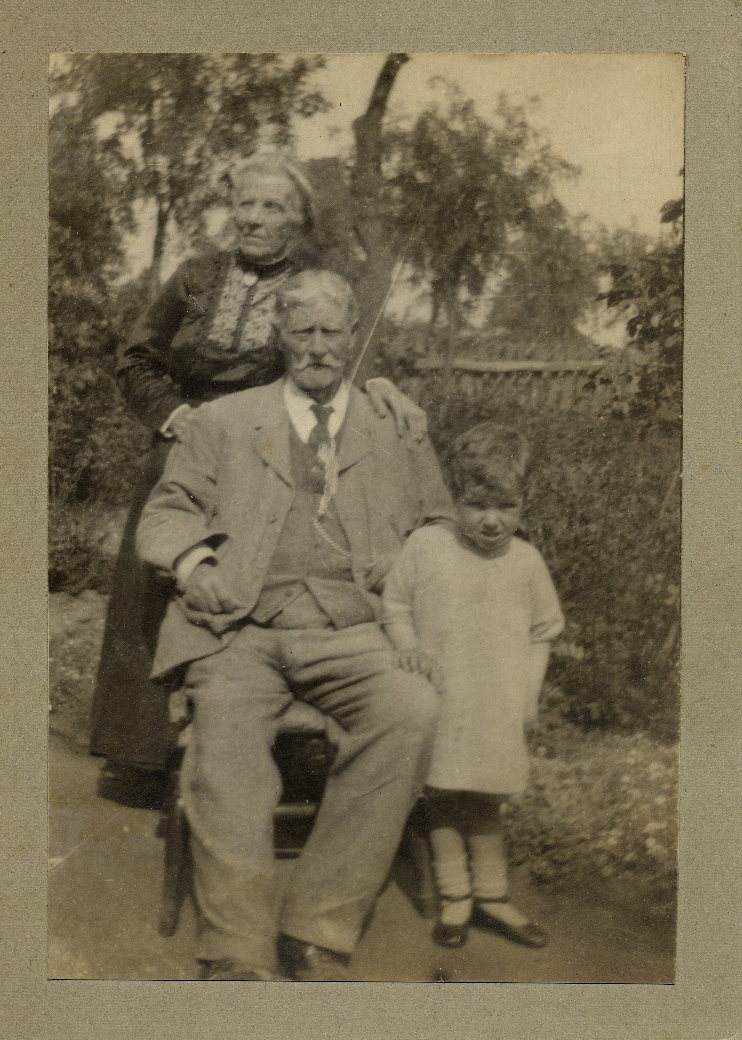

Another favourite bathing place was at the mill about two miles from home. Here the obliging miller would lift up the flood-gates so that we had the thrill of diving from the bridge into the water as it rushed and foamed below, and where we enjoyed being tumbled over and over by the current which carried us downstream for a hundred yards or more.

|

|||

|

The miller was a hefty man, weighing about eighteen stone. He was a member of the village cricket eleven in which we all took great pride. Throughout the spring and summer we would practise diligently, the two sides being made up from the team and volunteers. The side that picked Joe, the miller, was compelled to count him as a man and a half, so that the other side was allowed eleven, plus a boy, to make up the discrepancy. The blacksmith’s apprentice played long stop and I never tired of watching him in the field. Without variation he could stop the fastest ball simply by remaining upright and by clicking his feet and legs together so that one heard the ball crack like a pistol shot against his shins. Looking up at his impassive face one saw no trace of suffering from the impact, and longed to emulate such stoicism.

|

|

||

|

Picture supplied by Jacqueline Taylor nee Stewart

|

|||

| Joseph Morris (miller at Hoo Mill) and his wife Jane with granddaughter Jacqueline Stewart. | |||

|

|||

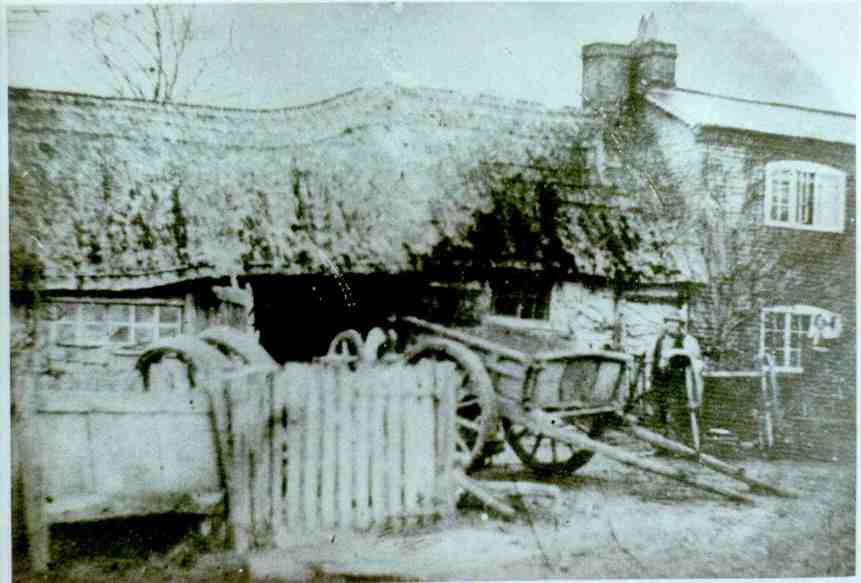

| The Smithy, Haselor c1876 | |||

|

It was at the blacksmith’s shop on winter evenings that the village would meet for boxing contests. Here, in a roughly improvised ring, where the furnace’s flickering light threw strange shadows on the walls and on the eager faces of the spectators, my brothers and I would take on any opponents, and often received a thorough hammering from the tougher men who, I think, must have mistaken our enthusiasm for physical strength, but it was useful training, and quite early in life I had cause to be glad of those bouts where I learned to keep my head and to use my fists.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Sunday at Haselor, when we were quite young, was a strenuous day as we elder ones started it by accompanying my father first of all to the eight o’clock service in the workhouse at Alcester, four miles away. While the parents went in the day cart our only means of transport was on foot, and by the time we had returned to the Vicarage, attended family prayers - taken by my mother - and had breakfast, it was time to get ready for Matins at Haselor.

|

|||

|

We always left the house in good time, but that was mainly in order to get up through the belfry on to the tower from which we had an excellent view, not only of the surrounding country, but also of the congregation as it climbed the hill to church. Directly we caught sight of father in his cap and gown with mother leaning on his arm as they came over the brow of the hill, we would scramble like a pack of monkeys down the various ladders in an effort to be seen by them robing for the choir in the vestry. It was an unwritten rule that the last man down should close the trap doors and on one occasion this routine nearly caused serious casualties. There were three ladders to be manoeuvred between the tower and the vestry, and Frank happened on this occasion to be the last man. After closing the trap door from the tower, he came down the first ladder like a disturbed cat burglar into the belfry, down the second, and then, in his haste to reach the vestry he jumped for the last ladder, missed it and fell into the vestry like a small bomb on two of the village choir boys, knocking them over and knocking himself out. He recovered consciousness quickly enough, however, to find himself being carried out by the sexton and the church cleaner - straight into the pathway of my father who, knowing his sons only too well, immediately cried out in anger more than concern “Now what has he been up to?” Had Frank not been in such a collapsible state he would, I am sure, have received corporal chastisement then and there. The poor boy was terribly bruised and shaken, but quite recovered in a few days. My eldest sister, Emmie and I went into the village after church to enquire for the two choirboys and found them none the worse. I remember one was playing a fiddle, and when I asked him what he thought had happened at the time, he said he imagined a bookcase full of heavy books had descended on him.

|

|||

|

Usually one of my sisters played the organ, but there was a time when this was undertaken by an extraordinary little man, dispenser to a doctor in Alcester. The temporary organist’s name was Floyd, and he used to walk out four and a half miles from Alcester for the different services. Our main interest in him lay not so much in his efforts at the organ, but in his fascinating hobby of collecting butterflies, fossils and other oddments.

|

|||

|

|||

| Rev. John Heath Sykes and Haselor Church Choir | |||

| Picture supplied by Sir John Sykes Bt. Great grandson. | |||

|

Imagine the astonishment experienced by us choirboys one Sunday when we looked up at Mr Floyd decorously listening to the sermon, his coat tails hanging over the organ seat, and saw from a pocket in one of the coat tails the spotted head and glassy eyes of a small grass snake protruding! This certainly was an event, and naturally the sermon was completely obliterated from our minds by speculations as to how soon the reptile would leave its unnatural home, and provide even more distraction by running berserk in church! Great was our disappointment at the snake’s final decision to retire once more into the tail pocket of the unsuspecting Mr Floyd.

|

|||

|

|

||

|

Reverend John Heath Sykes c 1884 Picture supplied by Sir John Sykes Bt. Great grandson. |

Reverend John Heath Sykes Picture supplied by Judy Turner |

||

|

Dinner at the Vicarage on Sundays was no mean affair. Father had to carve what in those days would seem a fantastic joint which we had smelt before breakfast as it was turned on the jack for twenty or twenty-two people. He was an excellent carver but by the time he had completed the first round, plates were already in need of replenishment.

|

|||

|

|||

| Billesley Church | |||

|

There was no opportunity for succumbing to the sleepy effects of repletion, however, for the next services began at three o’clock at Father’s other church at Billesley, a hamlet about three miles away. The parents always drove there, whilst we youngsters were packed off in good time to walk across the fields which ran along the foot of a wooded ridge known as Breach Hill. There were many reasons for dawdling on this walk, especially in the spring when there was eager competition in bird nesting. Wild strawberries grew in abundance on Breach Hill, and we often had to run hard to be in time for church after loitering in woods that were full of birdsong, and carpeted with wild flowers in an ever changing pageantry of the seasons. Sometimes, still breathing somewhat noisily from the exertion with which the last part of the journey had been executed, one of us would arrive after the single loud bell had stopped and when Father had already begun the service. It was impossible to slip into the tiny church undetected by his vigilant eye, and one’s flushed cheeks would take on an even deeper hue to feel rather than see the penetration of his glance reproving one’s lateness. |

|||

|

|||

|

Sometimes, after the service we would go with our parents into Billesley Hall where the squire and his wife, Mr and Mrs Crowdy lived. But more often we would start off as quickly as possible across the familiar fields again where even the spell of the woods was powerless to detain us as we hurried home for tea.

|

|||

|

This was a pleasant schoolroom meal which any onlooker would not suspect had been preceded by an adequate dinner, but I think our energetic programme on a Sunday necessitated generous nourishment. At the evening service in Haselor church my brothers and I again sang in the choir, and we looked forward to this as we were, without exception, keen on music and singing.

|

|||

|

Father’s predecessor at Haselor must have been a curious and unbalanced man, and to hear about his habits and idiosyncrasies would fill us with an astonished fascination. He lived, apparently in a room of a cottage belonging to a widow, close to where the Vicarage now stands. He shared his room with the woman’s son, but varied his habitat by living part of the time in the vestry. Here he housed his own coffin, and kept a store of food and other treasures in it.

|

|||

|

One evening a local farmer’s son was walking through the churchyard just as daylight was fading. He was about to pass the church door when it opened and Griffin, the parson, poked his head out and beckoned. The boy was rather frightened but obeyed, and followed Griffin into the vestry. Here, in silence, the coffin lid was raised and a box of oil paints extracted and given to the young visitor. Still maintaining the unnatural silence the parson then led the boy to the chancel door, let him out, and closed the door behind him. The recipient of this unexpected gift was very glad to run home as fast as he could.

|

|||

|

Another story of this eccentric man was that he had stretched across the corner of the church from his pulpit to the window a wire on which were suspended several doll-like figures. During his sermons he would sometimes pull the wire so that the figures danced up and down, and he would then refer to them as his seraphim and cherubim!

|

|||

| He always expressed a wish to be buried in church, but by the time his strange ministry came to an end, a law had been passed forbidding interment in churches. However, the resourceful Griffin had made his plans, and one can see to this day the place where, according to his instructions, he was pushed in from outside through an alcove under the north window, and where his name is engraved on the stone in the wall. My eldest sister who played the organ and practised during the week declared she could always smell ‘old Griffin’ when she passed up or down the aisle. Perhaps this was not a mere flight of fancy, as my mother, soon after going to Haselor, took a Colonel and Mrs Childs to look at the church, and all exclaimed at the unpleasant smell. Upon recounting the incident to various parishioners my mother was assured that it was undoubtedly the corpse of the previous vicar making itself felt. | |||

|

|

|

||

|

The inscribed stone "GRIFFIN" is where Cornelius Griffin was pushed in. This is just left of the downpipe, on the foundation stones. It was a wow moment after I had used a stiff brush to reveal this name on the 7th December 2008. |

|||

|

|

Within this Vault lies the Body of Cornelius Griffin. 21 years Vicar of this Parish who departed this life January 3rd 1867 aged 73 years | ||

|

|||

| Holloway Cottages, one of which was the home of Mary Savage. Now completely altered into one house and called Japonica Cottage | |||

|

He was not the only unusual character that held our childhood’s imagination, for there was still a belief in witches, and furthermore, that a certain old woman in the village was one. She certainly looked the part. Her name was Mary Savage. For no known reason she ‘took to her bed’ during our early years at Haselor.

|

|||

|

I remember being sent, as a small boy, with some cooked fish for her from my mother. The door of her cottage opened straight into the room where she lived. In response to my timid knock, a cracked voice bade me come in. I opened the door, and nearly fell into the room which was on a lower level than the threshold.

|

|||

|

There she was, perched up in bed, her wrinkled face yellow as parchment, with a hooked nose that almost met her pointed chin. She wore a greasy old nightcap, and was smoking a short clay pipe. Timidly I approached her with the fish which seemed to be my only security in this ominous atmosphere. Upon seeing the gift, however, she cried out in a querulous voice, ‘Feesh! feesh! I thought I told yer mother I didn’t like feesh!’ I stood there nonplussed, my eyes riveted on her witch like feature. Slowly she took the pipe from her mouth, and pointing with it to a tall wooden chest at the foot of the bed, she said in a low, impressive voice ‘I keeps ‘im in the top left hand drawer’. Overcome by a sudden fearful curiosity I whispered, ‘Who, Mother Savage?’ Her answer came in a sepulchral tone that made my hair rise from the roots. ‘The Devil’. Never had I covered any distance with such speed as I wheeled round and bolted through her door making for the safety of home!

|

|||

|

Yet even after that, I would find myself drawn irresistibly to her cottage as I grew more confident, and on one occasion she told me in a solemn and lowered voice of her experience in church many years before. ‘I looked up towards the East End, and there, plain as daylight, I saw the Virgin Mary. I half turned in my pew and looked at Farmer L - and sure enough he just nodded slowly at me, as much as to say, “Yes, Mary Savage, I saw ‘er too!”

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Charles Greenhill farmer at Walcote Manor | |||

|

At one time before she became bedridden, she had a quarrel with a certain Farmer Greenhill. The story was that some days after their dispute, the farmer was driving an empty wagon past her cottage, on his way to fetch a load of corn at harvest time. Mary Savage came out of her doorway and leaned on the garden wall with arms folded. As the wagon drew abreast of the waiting figure, the horses suddenly stopped, and, in spite of the farmer’s shouting and floggings, they would not move an inch. Exasperated, he turned to Mary and said, “Come on now Mary, I’m busy. You let the horses go.” With a malicious smile on her face she replied. ‘You can go on when I’ve a mind, and not afore’. After a considerable period of immobility she said quietly, ‘You can go on now, Farmer Greenfield’, and the horses went into their collars and proceeded up the hill.

|

|||

|

It was so firmly rooted in the minds of the villagers that Mary was a witch that one woman told me she would never let her enter her house. One day Mary came to the gate of this old woman’s garden, but, as she recounted ‘I watched ‘er stop all of a sudden. For why? Because I’d an ‘orseshoe nailed over my front door, and witches can’t face ‘em, so ‘er just turned round and walked away.’

|

|||

|

Another woman who lived to be ninety-four told me with great solemnity that some time after Mary had died, a cat had come into the house which she declared was Mary reincarnated! ‘Aye’ she said, ‘er come in the other day, and I got the mop and chased ‘er out. I knew it was Mary - ‘tis an evil cat all right’. The same woman, on another occasion chased the cat away with a broom, and was heard to say ‘Confound your politics!’

|

|||

|

One of my favourite errands was to take shoes to be mended by the village cobbler, Bob Lane. (Bob Lane lived at 'The Beehive', Haselor) The front room of his cottage was ‘the shop’ and there he would be sitting in the window, his head bent over his work. His mouth seemed always to be full of nails which he scarcely troubled to remove as he talked away and continued his work. But he must have had long intervals when there were no nails between his lips, for he was most successful in teaching his tame bullfinch to whistle. The door leading to the stairs behind him was kept shut, and in a cage in the dark, halfway up the stairs, was one bullfinch which he had taught to whistle perfectly the chimes of the church bells with their changes. I am afraid I never questioned, even in my mind, the plight of this feathered prodigy purposely shut out from the light in order to encourage concentration on the whistling lesson. Indeed it seems strange now to remember with what pleasure we would participate with grown ups in what was then considered to be legitimate luxury, but which now seems inexcusable - a feast of small singing birds, roasted and served on a large dish.

|

|||

|

Tom Lane, the cobbler’s son, was the proverbial village idiot. Rumour had it that he had been knocked silly when an infant. The poor chap was quite harmless, which was just as well, as his father, Bob, used to get very exasperated with him, and one day ejected him from the cottage shouting in a loud voice, ‘You get out me ‘ouse, you ill-bred feller you’!

|

|||

|

Poor Tom Lane! My most vivid memory of him is in Haselor Church where he used to pump the organ. Each time he made the necessary downward movement, he would turn his head over his shoulder, and in a rhythmical way would make all the gestures and noises of spitting. This inexplicable mime would go on through the whole service. One Sunday a heated altercation took place between Tom and one of my sisters who was playing the organ. The number of a hymn had been announced, but, unknown to Tom and my sister, the bellows had split. Instead of the opening bars on the organ my sister’s voice was heard, ‘Why don’t you blow?’ followed by an equally irate rejoinder from Tom, ‘Why don’t you play?’

|

|||

|

|||

| Servants at the Haselor Vicarage c1893 | |||

| Left on picture, Sophia Roberts nee Groves and right on picture, Rhoda Leach nee Phipps, grandmothers to Judy Turner nee Roberts. | |||

|

Picture and information supplied by Judy Turner |

|||

|

Tom had a sister who, for twenty-five years, was a housemaid at the Vicarage - which reminds me of another girl who left the village for domestic service in a town. One day, this girl, Hetty, came home on holiday for the first time since going into service. I happened to be visiting an old couple in the parish, and asked Mrs Washbourne whether she had seen Hetty. ‘Ave I seen ‘er? ‘Ave I not seen ‘er? ‘Er’s come ‘ome covered all over with ribbons and furbelows, an’ there ‘er was yesterday, walkin’ down the village Street with ‘er ‘ead in the air - as ‘aughty as a pump!’ a simile which struck me as being singularly descriptive.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Mrs Washbourne lived in one of the cottages on the right.

Demolished late 1950's for a new house "Highfields". Tom Lane lived at 'The Beehive', on the left of picture. |

|||

|

Country people have no false modesty, nor did they spare one’s feelings where their own ailments were concerned. One day, on looking in at old Bob Lane’s, I was surprised to see him standing about miserably in his shop. Upon enquiring tactfully for his health I was somewhat unprepared for his reply, ‘Well, Master Willie, I ain’t too grand. Ye see, I’ve got a little boil on my bottom, an’ I can’t sit down nor do nothin’!

|

|||

|

One never knew what confidence would be given to the seemingly harmless greeting of ‘How are you?’, and amongst the less crude replies was old Robert Groves’ who, pointing from head to his waist said, ‘Oi be all right from here to there, but m’legs be no good to me’.

|

|||

|

A local saying that used to puzzle me as a boy was the word “unkid”. An old man told me it was “unkid” walking through the churchyard late at night. Another told me not to walk across the meadows after heavy rain or flooding as I should get “watchered”, and an apt expression used by a villager who suffered from headaches was “me ‘ead be all of a mumblement”.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

One old man who used to live in a cottage beside the church, and furthest from the village, had to walk through the churchyard on his way back from the ‘local’. He invariably carried a loaded muzzle gun. One night he was coming home through the churchyard, and as he rounded the corner of the church by the east window, he saw a strange white spectre near the wicket gate through which he would have to pass. Up went his gun and a shot rang out on the still air. The whiten head toppled to the ground, but the sound was too substantial for the substance of a ghost. He approached with wariness the object of his marksmanship, and found that he had blown off the head-shaped top of a newly erected tombstone. For decades it has lain in the grass with the shot mark on it. | ||

| This headstone which was eventually repaired is still in the churchyard. | |||

|

The old men in the village used to recount the most hair-raising happenings to the all to credulous audience consisting of my brothers and me. They were nearly all of strange things that happened at night which made them all the more exciting. One described a black dog as big as a calf that had been seen on various occasions lurking round the pillar box in an isolated spot at the far end of the village, and it was with a certain trepidation that we took letters to post after daylight. Nevertheless it was a more hackneyed kind of ghost who really terrified us by the description of her as a headless woman carrying her head under her arm, to be seen on wild nights at the cross-roads on the way to a deserted farm.

|

|||

|

A story which we believed implicitly until we were old enough to see the catch in it was of the big stone on the top of Church hill. This, we were told “when it hears the clock strike midnight, rolls itself all round the hill, and settles back again in its accustomed place”. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Picture supplied by Judy Turner |

|||

| This is the stone which was called "Old Money Stone" or "Treasure Stone", and featured in childhood fantasies, situated just outside the now enclosed church path. It was moved to its present position, early 1970's. | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

There was also the account of a ghostly highwayman told us many times upon request mainly because the teller dramatised a wayside robbery with histrionic verve suited to his husky words, ‘..an’ the masked highwayman pulled out ‘is revolver, threatening’ like …..’.

|

|||

|

Although my Haselor memories are mostly of events during long summer days, I remember some exciting experiences when a party of us went out ‘bat-fowling’ at night - a not uncommon past time in the country in those times. Our main hunting grounds lay around the hayricks, ivy-covered walls and hedges.

|

|||

|

Armed with rather unwieldy clap nets which consisted of two long poles joined by a width of fine meshed netting, two of us would stand on one side of a likely hedge, one on the other, and two beaters on each side with long sticks would drive the quarry towards us. Of course we caught a variety of flying creatures including many sparrows, and on one occasion the catch was novel but not without embarrassment. The fact of our hunting ground being on someone else’s property did not deter us, and on the particular night in question we were disturbing the ivy on a big house when the sudden opening of a little window synchronised with the closing of the clap net, and the upturned faces of four astonished bat-hunters saw that the catch was no less than the protruding head of the woman householder. Her wild screams certainly added to our own shock, and, releasing our trophy, we made off as hard as we could go, our only aim being to put as much distance as we could between ourselves and the house. Strangely enough, we heard no more about it, though a haunting sense of guilt accompanied us for some time.

|

|||

|

One of my brothers went to see an old man in the village one very hot summer’s day, and in the course of conversation Hugh was asked “ave you ever tasted my ‘ome-made wince, Master High?’. On being assured that this had so far been denied him, the old man started hunting about, and said he couldn’t find a vessel to draw some into. After a while, he emerged with the wine in a chamber pot, and in response to Hugh’s undisguised amazement said, philosophically, ‘To the pure, all things be pure’!

|

|||

|

Some of the villagers had Biblical names, one old man having been christened Mephiboshith (‘out of my mouth proceeds reproach’!). His wife, to our amusement, always called him ‘Fibby dear’, and they had a son called Nimrod. One girl was named Hephsibah which has a much more preferable meaning ‘my pleasure’, and I think my father was hard put to it at times when there was a christening, wondering what might be sprung on him at the font!

|

|||

|

I was down in one of the fields one day when the men were mowing the grass. Everything done by work-worn hands in those days, and it was quite impressive to see the extent of mowing that could be done by four or five men in one day. Anyhow, I had our spaniel with me, and he was having a high old time unsuccessfully chasing after the swallows as they skimmed over the mowers and unmown grass. One of the men became wildly irritated and shouted out me, ‘Get that black Ellian out of ‘ere. You lads are a perfect nuisance and don’t let nothin’ abide. ‘ell’s so full of parsons’ sons now, their legs are ‘angin’ out of the winders’.

|

|||

|

My brothers and I did quite a lot of bicycling on what is now known as a ‘penny-farthing’, but when it first appeared it was called a ‘spider’ or misleadingly ‘an ordinary’. We tried at first to learn on a fearsome contraption which initiated the description and name of ‘bone-shaker’. This had a front wheel slightly larger than the back one, but differed from the ‘penny-farthing’ in that it was all wood and iron, and you could hear it coming along the road a mile away. There were no rollers in those days to roll in the stones that made the highways and lanes. This was all done by the everyday traffic, farm carts and so on. Consequently the long rides we had on the noisome “spiders” were not without jeopardy, and at first we found them extremely difficult to mount. You had to put your left foot on the little step over the small wheel, taking hold of the handle bars, and hopping along with the right foot on the ground to get a bit of impetus. Then came the jump for the saddle, which, if you landed a bit short of it meant landing on the back of the saddle which being made of very thin strips of leather over very unresisting iron, could be extremely painful to say the least of it. There was alternatively the possibility of over-shooting the mark and soaring over the handle-bars bringing the machine down on top of one which was apt to be injurious to oneself and the ‘Spider’. But after a time, we older boys gained confidence and had tremendous fun practising different ways of dismounting. We invented six variations of this. The most difficult one was jumping over the front wheel, turning one’s body in the air and landing on the ground in front of the big wheel. Another trick was getting up to high speed and then leaping off on the near side, and taking great strides, holding the bicycle in the air. One of the worst falls I had was one evening going down an incline, pedalling as hard as ever I could, with a cricket bat under my arm on my way from a practice match in a nearby village. All I remembered was the road coming up to meet me. Of course I was knocked out by the impact, and the first thing I saw on gaining consciousness was from badly cut hands, elbows and nose. Fortunately the blacksmith had seen this happen, and came down the lane and carried the bicycle up to his smithy for repairs. It was discovered that the cause of the mishap had been due to the big wheel having broken clean in two. Such is the resilience of youth that I walked down the village, borrowed a bicycle from a farmer friend and rode off to Hoo Mill to join my brothers in bathing. I was greeted by hoots of laughter, as I must have cut a somewhat comical figure covered in blood and dust, though the funny side of the episode had not struck me till then. The bathe doubtless did me good in the circumstances, and although I slept the sleep of exhaustion that night, in the morning I could hardly move for stiffness and multiple bruises. Another time, my bike hit a stone and turned right over on me. Unfortunately I had my hands in my pockets, and when I got to my feet found one handle-bar bent nearly double, and both my wrists aching acutely. Anyhow, I somehow managed to push the bike to my friend the blacksmith who straightened the handlebar for me, but when I tried to mount and ride away, the pain all up my arms prevented me from putting any weight on them. However, the blacksmith lifted me up, gave the bicycle a push, and off I went on my way, though it was only possible to use one hand on the bar that being fairly painful. When I reached the village school I was faced with the difficulty of getting off the machine, so had no choice but to fall off. After this, I went to the doctor who, on examining me, found I had sprained one wrist badly and strained the other. I emerged with both arms in slings, and had to stay out of action for about ten days, which I found most frustrating.

|

|||

|

From early boyhood I had always been interested in carpentry though what I did I had to do entirely by trial and error, but some of my efforts were quite successful, especially with rustic benches and pergolas for the Vicarage garden, hutches for the tame rabbits, ferrets and guinea-pigs, and my piece de resistance, of which I was inordinately proud was a pigeon-cote which housed several fantails. Of course I could not afford books on carpentry, and had no facilities for my work, except down in the cellar of the house which were apt to need constant cleaning owing to the dampness of the walls. I did my best to turn into a carpenter’s shop with racks to hold my tools, all difficult to collect from the small sums of money that ever came my way, though my brothers and I constantly tried to evolve ways and means of adding to the kitty in as legal a way as possible. Sometimes our ingenuity in this matter rather strained or even bent strict legality. I used to work down in the cellar after dark by candlelight, and I think my parents were very long-suffering, as, being immediately under the drawing room the noise of hammering and sawing must have been rather disturbing, to put it mildly, especially when they were indulging in an after-dinner nap.

|

|||

|

Timber could not always be had ‘for free’. We were therefore delighted when the large boards in the church with the Commandments inscribed on them were pronounced obsolete by the Parish Church Council, and Frank obtained permission to use them for making a garden seat. As his theory was rather more imaginative than his creation, the seat proved to be most uncomfortable so that it was seldom used, and was always referred to as ‘the holy seat’.

|

|||

|

Many a free hour I spent in the ironmonger’s shop at Alcester, examining and admiring the many tools and implements which I could never afford.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Entertainments in the village school provided exciting opportunities for my carpeting enthusiasm. It was with eager anticipation that I looked forward to the preparations beforehand, fixing a platform for the artistes and generally assisting with the improvisation of various furnishings.

|

|||

|

|||

| Herbert Coney lived here and died in 1895 | |||

|

The position of the piano was always a bit of an anxiety, but one joyfully entered into the practising of glees with the choir in testing the stability of the boards which were generally much appreciated and very well performed. One of the most amusing items on such programmes was provided by a draper, Mr Holland, from Alcester, whose comic songs and sketches kept us in fits of laughter. Then there was Mr Coney, a farmer who had a very forced way of singing ‘Then let me like a soldier die’, insisting on a few short bars being blown on a cornet at certain points to give what he thought was a stirring effect, but as the various volunteers with the cornet were not very proficient, the result was often more humorous than was intended. A popular ‘turn’ was the song, “Three Old Maids of Lee’ sung by three men whose fronts presented the appearance of three old maids, and whose backs when turned to the audience, revealed three young maids. The way in which the performers entered into the spirit of the thing, used to bring the house down.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Upton Manor |

|||

| John Smith Perks lived here with 6 sons and 2 daughters. George, Fred, William, Harry John, Frank, Mary and Agnes Ellen. Only one son and one daughter married. The daughter Agnes Ellen being my grandmother. | |||

|

John Finnemore, Walcote Farm |

|||

|

Perhaps the star turn was a farmer called Perks who really was a natural comedian, and could have made a name on the halls. Each of Perks’ ‘turns’ was followed by one done by his brother, Fred who only ‘rendered’ the most sentimental songs. He did this with such emotion and melodrama that it was often difficult to be sure whether or not he was also aspiring to the role of a comedian, and of course this only added to the general hilarity.

|

|||

|

It was always a great day when the mowers came to mow the fields around us. They used to begin at 3.00 am, and each one brought with him his little cider barrel holding about a gallon and a drinking horn. They also wore a strap round their waists with a leather thong behind to hold the rubber for sharpening their scythes. The rhythm of their movement was an unforgettable sight, and one which is no more seen. Sometimes we used to follow them, and I remember when the man in front of me cut over a mouse’s nest, and I saw little pink baby mice inside the nest. I put them in my handkerchief, and carried them home very carefully, hoping to rear them in a box lined with cotton wool, but regretted their untimely demise.

|

|||

|

Reaping was very slow job in those days. The reaper would take a handful of standing corn in the left hand, and with a sickle that had a serrated edge he would draw it through each handful. Farmers always allowed the cottagers to go into the fields after the corn had been carted, so that they could glean the grains left on the ground, and they used to collect enough to make a small rick. Then, when the farmer threshed his own corn, it was an understood thing that he would thresh theirs as well. They used to make the most delicious bread out of it. My mouth still waters at the memory of the nutty smell that would draw me into a cottage where bread-making was in progress.

|

|||

|

One very vivid memory comes to mind when I nearly lost a leg. A farmer was carting his hay in a 4-wheel wagon, and the three horses were being driven by an old farm hand whom I knew well. I ran after the wagon, and took hold of the back of it, swinging my foot on to the hub of the nearside wheel. As the wheel went along over the rough and uneven ground, the hub, to my horror opened in and out. My foot slipped into the revolving opening. I yelled at the top of my voice, and providentially the old man heard me, and pulled up the horses just in the nick of time, as further movement of the hub would almost certainly have taken my foot off. With the help of another man, they held me up still trapped by the wheel, while another man went up to the nearest farm for a wagon jack with which they released me and then carried me home. My parents, fortunately were away at the time, but our governess was in a dreadful state.

|

|||

|

Even before I was old enough to carry a gun I was very keen on accompanying anyone with a gun, and on every occasion I would take the opportunity of walking round the farms with their owners to watch them shooting rabbits or rooks. Above everything I looked forward to the days when it was my turn to go out with my father, to carry the cartridges and hold the dog. When I was nearly fifteen, I was lent a small muzzle gun with very short barrels. This antique, and not too safe weapon gave me many stolen hours of exciting sport, and I never tired of practising my marksmanship on pigeons, rabbits and rats. The muzzle loader was especially lethal when one ran short of percussion caps which were put on the nipple to explode the black powder. To improvise in such circumstances, I used to pull of the head of a match, place it on the nipple, and put a used cap on the top. When the trigger was pulled the match head would sometimes ignite the powder at once, but when at other times the ignition was delayed the bang which unpleasantly sudden could almost through one off balance. I also had a little fox terrier named Charlie, and when the farm I intended visiting was some distance away, I would ride my penny farthing with my gun under my arm, Charlie running behind, and my pet ferret on my shoulder. The ferret would often lick my neck as we sailed along.

|

|||

|

The first pigeon I ever shot was on my return from a farm near home. I saw it up in the topmost branches of a tall poplar, but was very doubtful as to whether I would be able to get a shot at it, as the short barrels of my gun might not carry far enough. However after manoeuvring to get as near as possible without being seen, I took aim, shot, and, to my great delight was rewarded by the pigeon tumbling down dead at my feet. I took it home in great triumph, plucked and dressed it for supper, and had it cooked, and to me it was the best pigeon I had ever tasted. Encouraged by my success with the fun, a few days later I saw some distance away a rabbit motionless in it own ‘forme’ on the side of a hill. As there was very little cover, I began stalking it on my tummy until, after a time, I was near enough to shoot. When I went to pick it up, I found, to my intense disgust that it had a wire round its neck so that all my careful and time consuming stalking had been in vain.

|

|||

|

On another occasion I was accompanying a farmer and his gun over his land, when we saw a stoat carrying something in its mouth. The farmer fired and killed the stoat, and found it had been carrying a partridge’s egg. On hunting about we discovered the partridge’s nest with about a dozen eggs in it which the old hen partridge safely hatched out in due course.

|

|||

|

Using a muzzle loading gun was a rather long and tedious affair compared with the later breach loader. The former had to be loaded at the wrong end so to speak, the ram rod was attached between the barrels underneath and was used to ram wads of brown printed paper on to the black powder and shot. The procedure was first of all to pour the powder from the powder flask down the barrel, ram a wad of paper down on to the powder, pour some shot down the barrel and stuff another wad of paper on top of the shot. An old saying in those days was “If you want to kill dead on the spot, ram your powder and not your shot” or “if you want to kill sure and dead, ram your powder and not your lead”. Then we were taught, see that the powder comes right up in the nipple and then place a copper percussion cap on the nipple and it is ready for shooting. This meant that one had to carry a powder flask, a shot pouch, a box of percussion caps and a supply of paper. The amount of powder and shot could be regulated by a spring on the flask and pouch.

|

|||

|

The first breach loader I had when I was sixteen was a sixteen bore Purdey underhand action, bought for me by my father. It was an old gun but in very good condition, and I used it right up to the time when I joined the Army, when I exchanged it for a 54 inch bicycle of a village friend when he was off to the South African war.

|

|||

|

When my brother Jack died in India and his effects were sent home, his gun was passed on to me by my father, and it had a long and eventful history. Jack had bought it from the ironmongers in Alcester for £5.00 in 1893, a double barrelled one with which I shot for many years in England, Ireland. Scotland and South Africa in 1898. When I left South Africa in 1904, my youngest brother, Charles, working for De Beers in Kimberley, wrote to ask me to get him a gun. and I decided to lend him this one. He did a lot of shooting with it out there, but unfortunately lent it, ostensibly for a short time to a man who went suddenly bankrupt. When Charles wrote to him for the return of the gun, he found that it had been sold in an open sale by the borrower. Charles was very upset about this, as he knew how I valued it, so he said the man must do his best to trace its whereabouts, and get it back. After some considerable time, the gun was traced, but reported to be in such bad condition that it needed extensive repair, as the stock was broken, and due to bad usage was not fit to return as it was. The man, however, had improved financially and sent the gun to England where it was thoroughly overhauled. In time Charles received it back again as good as new. When Charles returned to England, he sent it back to me, so that I shot with it for some years, until I replaced it with one from Powells of Birmingham. This reminds me an amusing expedition I made with my Father to that firm, when he went to try out a gun they had built for him. When visiting Birmingham, he always wore a top hat and frock coat, and thus clad he arrived at Powell’s shooting ground. I always wish I had had a camera on that occasion, for there he was, with his coat off, in his white shirt and clerical ‘bib’, tall hat on the back of his head, firing at different objects with his new gun - and incidentally hitting them all!

|

|||

|

It was that day, in the early part of the 20th century that I found a good second hand gun for £15.00. This was a considerable sum in those days, especially for me, so my father paid half and I used that gun for nearly twenty years during which time I became known as ‘Dead eye’ for accuracy.

|

|||

|

The gun that had been sent to England for repair I lent to my eldest son Jack who was in the Army. He had it in India and Egypt between the two wars, and when he returned it to me. I lent it to my third son. Paul, but when he was in Africa he lent it to someone who lost it, and it was never traced or returned, a sad ending to its story, as even when my brother Jack had had it, it must have travelled all over the world. Incidentally, this brother had gone to sea in his teens as a member of the crew of the famous sailing ship, the Cutty Sark, and I regret that no account was ever written of his experiences, for he was a very attractive character, popular wherever he went and with a rich and articulate sense of humour, and a gift as a raconteur who could keep his listeners at a high pitch of excitement, or in a collapsible state of laughter.

|

|||

|

Years later, when I was returning from South Africa on a P and O boat commandeered for troops, I asked the Captain whom I got to know during this voyage whether by any chance he had ever come across a young P and O officer, Jack Sykes. ‘Indeed I did’ he replied, ‘and he was one of the most popular officers we ever had in the P and O’.

|

|||

|

Corporal punishment in our early years was generally administered by a nurse who used a tin mug or flat side of a brush on our back sides. Although we would often resort to the WC as a place of refuge from the threat of adult retribution, we had an equally useful escape route in my Father’s treasured onion bed. Both parents were keen gardeners, but Father’s greatest pride was in his onion bed which stretched right across the width of the kitchen garden, taking up about six or seven rows. On various occasions we avoided a thrashing by making a bee line for the onion bed, leaping to the far side of it, and thus defeating our would-be chastiser who would remain in a hopping state of agitation on the opposite side as the onion bed must not be trampled on.

|

|||

|

|||

|

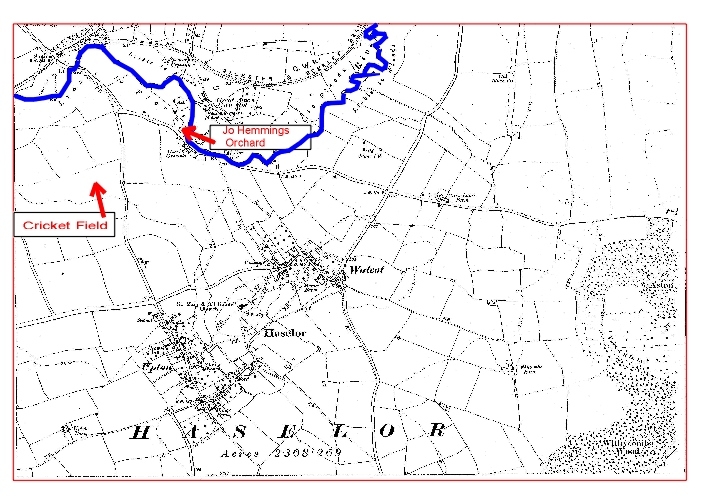

On the way to and from our swims in the Alne river, which we visited for this purpose in the summer sometimes four times a day, we would pass through an orchard where there was a very special apple tree with summer fruit on it which we used to take rather heavy toll. The orchard belonged to a farmer, Jo Hemming, a shy and kindly man who never complained of our robbery.

|

|||

|

We had two cows, Cherry and Mulberry, several pigs and fowls as well as tame rabbits, pigeons, guinea pigs and ferrets. We also managed to take sparrow hawks from their nests when fledglings, train them and sell them by advertising them at 6/- each in ‘The Exchange and Mart’ a very useful addition to our erratic finances.

|

|||

|

I remember my Mother as always fully occupied in a ceaseless variety of ways at home, in the garden, making pickles and jams, and village, as well as having quite a social life.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

The three tall gravestones belong to the

Sykes's family. The one nearest the fence at the back is the grave

of Lt

Colonel William Sykes, the writer of this story. More will be mentioned about the other Sykes's graves in the next edition of vicarage life. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Footnote by John Finnemore. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

The story about the large stone rolling around church hill and the shooting at a ghost which turned out to be a headstone was also told to me in my childhood in the 1940's. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Joseph Hemming, farmer, lived at Haselor Grounds. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

The practice of keeping songbirds in the dark still goes on, in some Mediterranean countries. The idea is that when the birds are brought out into the daylight, they think it is spring and cannot stop singing. The singing then lures other birds to the area, where they are trapped by the use of nets, cages or glue. The songbirds are a gourmet speciality and are sold in restaurants and butcher's shops. There is a more modern way of catching songbirds, by the use of electronic sounding equipment. Millions are caught every year. This information was found on the internet. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

The cricket pitch was in the field where the stables are in Pelham Lane. |

|||

|

Cottage beside the church. I have a map which shows a building near the church. More research needed. |

|||