Boneshaker (or "bone-shaker") is a name used from about 1869 up to the present time, to refer to the first type of true bicycle with pedals, which was called "velocipede" (from the Latin for "fast foot") by its manufacturers. "Boneshaker" refers to the extremely uncomfortable ride, which was caused by the stiff wrought-iron frame and wooden wheels surrounded by tires made of iron.

|

Haselor Memories |

|

|

when living at Haselor Vicarage |

|

| by Francis (Frank) William Sykes (1864-1945) | |

| (Francis (Frank) William Sykes, son of Rev. John Heath Sykes, Vicar of Haselor 1867-1912) | |

| This fascinating account of Haselor Memories when living at Haselor Vicarage in the 19th century. It was only known to me in 2008, after I found out that Sir John Sykes had photographs of Rev. John Heath Sykes, Vicar of Haselor. He told me that his grandfather had also written about living at Haselor Vicarage. | |

| John Finnemore, Walcote Farm | |

|

I was born at Bishopton, an adjacent hamlet of Stratford-on-Avon, in 1864, the eldest son of my father, the Rev. John Heath Sykes, a country parson who was vicar of the parish of Haselor and rector of Billesley. He was educated at Eton and Oxford and was of the type which, alas, is almost as extinct as the "Dodo". |

|

|

|

|

|

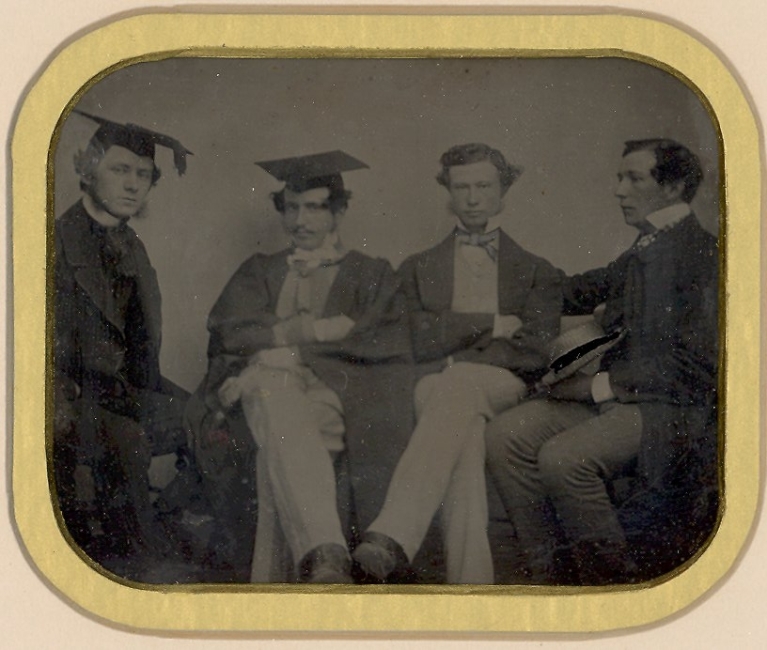

2nd from right:- John Heath Sykes at Oxford c1855 |

|

|

Picture supplied by Sir John Sykes Bt. |

|

|

|

|

|

JHS c1855 |

JHS c1884 |

|

Pictures supplied by Sir John Sykes Bt. |

|

|

He was a generous-hearted gentleman, possessed of an infinite fund of humour, an excellent shot and a rabid Conservative to whom the name of Gladstone was most abhorrent. He was a good walker, an interesting talker and, like most parsons in those days, had a quiverful of children. There were 14 of us 8 sons and 6 daughters. When we dispersed after breakfast, on our several occasions, he used to say "Ah, the Sykes family will now be pepper-castoring themselves over the neighbourhood". Anyway wherever we went we were most heartily welcomed as his progeny by high or lowly. In a long life I have no hesitation in saying that I have never met anyone quite like him, certainly, none for whom I have had a greater respect. As far as I was concerned he spared not the rod, so by no effort of the imagination could I be accounted a spoilt child. This tribute to his memory may therefore be taken as genuine. |

|

|

Many of his sayings, wise and otherwise, remain with me to this day. "Always go to the fountain-head if you want anything." "Never trust a dissenter or a man who squints." "Always acknowledge money or a lady's letter by return of post." "Beware of holding yourself too cheaply." "Look here, Frank, I'll have no d----d nonsense as your Uncle Arthur would say!" |

|

|

I remember asking him one day whether he was a High or Low Churchman. His reply was, "Neither, but I hope I am a good Churchman." He was. He referred to vestments and genuflexions as "ecclesiastical millinery and gymnastics." To a fellow parson who turned up at tennis in a biretta and cassock he remarked, "My dear D., how do you expect to play in petticoats?" |

|

|

His judgment about men and things was seldom at fault, but although he wrote and preached excellent sermons, he was inclined to mental inertia, and, having perpetrated one, it would have to do duty for years; his sermon cupboard contained a bulky collection of his own and his father's, each being docketed with particulars of when and where last preached. |

|

|

When he first took over the living of Haselor in 1867, it had the name of being one of the worst in that part of Warwickshire, that is from the parson's point of view, and although not handed down to posterity by a Shakespeare like "Drunken Bidford" (a few miles away) it had achieved some notoriety in general looseness of character. This may, no doubt was, more or less due to his eccentric predecessor whose "goings on" were more amusing than edifying. It was said that he kept his coffin in the vestry using it as a larder for his provisions there was no vicarage in those days and presumably he took up his quarters in the church whenever convenient. He had a contraption of glass dolls, so arranged on wires, fixed on the altar rails, that they could be made to dance, which were referred to by himself as the Cherubim and Seraphim. One can imagine the intense awe and delight of the children, who, from the safe distance of the back pews could see the figures work. My father was told by one of the village ancients that he had held a bucket of whitewash whilst either the incumbent or one of the churchwardens brushed a coating over a parish bequest to the poor, painted on the wall of the vestry, for reasons best known to himself. And there today they lie at rest, not many yards apart, the man whose name was a byword for unworthy conduct, and the other who after 45 years as faithful parish priest, left behind him a memory beloved and honoured by three generations, and a church restored both as to its structure and the beauty of holiness which marked its services. |

|

|

Click here for newspaper cuttings of the "Haselor Parsonage House and Church Organ Funds". |

|

|

|

|

|

Picture supplied by Sir John Sykes Bt. |

|

|

The "dear old Guvnor" in due course had a good organ installed and a surpliced choir of men and boys about a score who were trained by himself. Two choir practices during the week and occasionally one extra after service on Sunday with my mother or one of the sisters presiding at the organ. |

|

|

Part of an article in the Alcester Chronicle 20th June 1868.

HASELOR.

OPENING OF THE CHURCH ORGAN

This usually quiet village, presented on Sunday last, quite and unwonted appearance, in consequence of a large number of strangers who attended the parish church, at both morning and evening service on that day―the occasion which called them there being the opening of the new organ, of which the church has, we believe, hitherto been destitute. Haselor is situated near the river Alne, about 2½ miles north-east of Alcester, but as it lies some distance to the left of the turnpike road between Alcester and Stratford-on-Avon it is comparatively unknown to the travelling public. The church of Haselor is pleasantly situated upon a hill, and is partially embosomed with trees, and country around is agreeably diversified with hill and dale. The church is an ancient structure, with nave, chancel, side aisles and square embattled tower, containing 2 bells, surmounted with pinnacles, and was, together with the churchyard, founded by one of our Norman Kings (though which is uncertain), to the honour of Christ, the Blessed Virgin, St. Lawrence, and All Saints, and was originally endowed with a house for the Parson and two Yard Land lying in the fields of Haselore and Walcote; as also certain pasture grounds to the same belonging, with a certain Place and Croft lying opposite thereto. This grant was afterwards in the reign of Henry II augmented with an ample addition. The The house for the Parson has, from time immemorial, ceased to exist, but there is now a prospect that a vicarage house will shortly be erected. In the early part of 1867 the living of Haselor became vacant by the decease of the Rev. Cornelius Griffin, who had been vicar for 20 years: and on the 12th of April following, Rev. J. H. Sykes, rector of the adjoining parish of Billesley, was instituted to the vicarage of Haselor; and in a short period of fourteen months he has succeeded in obtaining subscriptions to the amount of £1981 2s. 9d. towards the erection of a vicarage house, including the site of the same. |

|

|

How it all comes back! The perspiring boy at the bellows (too often myself), the reek of the farmyard from the boots of the choristers, the dim light from a few isolated candles "Try over the psalms for next Sunday Barnes for the first sing it to la, trebles first that won't do, you're all as flat as ditchwater try it again." And so on altos, tenors and basses then with a look of relief, "Now altogether," when we got warmed up to the work and gave forth a cheerful noise. |

|

|

But these innovations at the beginning of things stirred up the congregation more than a bit. On the first occasion when surplices were introduced there were murmurs of "Popish games", "They bain't no good", "That's 'ow Aston Cantilow went" (the next parish with a high ritual) and similar hostile remarks. When the psalms were sung several of the congregation walked out of church. My father, seeing this, invited anyone objecting, to meet him in the vestry after service. Two only turned up, one of the churchwardens (a very low churchman) who subscribed to "The Rock", and the village carpenter who was the official organ-blower. |

|

|

"Well, Mr H. what is your objection?" the first was asked. "I don't like it Sir, that's all," was the reply. "A woman's reason" remarked the guvnor with curt contempt. "Now William what about you?" "Well, Sir, I think it's wrong, we bain't used to such things." "Now look here William" was the retort, "if I came into your workshop when you were making a wheelbarrow and told you that you were making it wrong, what would you say?" "I should tell you to get out and mind your own business." "Quite right William, and that is exactly what I wish to tell you." There was no more trouble. |

|

|

William was the village carpenter, William Knight, living at The Cider Mill, Walcote. |

|

|

Billesley parish (two miles nearer Stratford of which he was rector) boasted only a score or so of inhabitants which however included the squire of Billesley Hall. Tradition has it that Billesley was at one time quite a flourishing place but had been depopulated by the plague in the reign of Queen Anne. It is recorded that Shakespeare and his small daughter used to walk across the fields from Stratford to attend service, a sweetly pretty walk through Upper Billesley with many gates and stiles en route. |

|

|

|

|

|

Billesley Church |

|

|

The church is probably one of the smallest in England but always large enough for the congregation. The reading desk and pulpit was a two-decker arrangement with red velvet hangings and a huge bible with all the interior s's shown as f's. One of my brothers being invited to read the lessons made a most frightful hash of it by treating them all as f's to my father's consternation and intense amusement of the choir, consisting of two other brothers and myself. |

|

|

|

|

|

The old squire's pew on the left. The squire was Mr Crowdy of Billesley Manor. |

|

|

Nestled in a corner of a big square pew surrounded by a top-dressing of brass rods and stuff curtains was the old squire whose devotions and slumbers were thus shielded from the common gaze. |

|

|

From the full-dress effort of a Haselor service to the rather dismal and threadbare devotions of Billesley was a big drop and, as boys, we regarded a Sunday afternoon service there in mid-winter as something to be avoided especially when a doleful hymn such as "Days and Moments" topped up the proceedings. |

|

|

Prior to his appointment to Haselor, my father had officiated at Billesley for 7 years. A primitive state of affairs equally prevailed there. There was no organ, the music being provided by an orchestra composed of a fiddle, bass viol, trombone and clarinet. The performers used to walk over from Wilmcote (where Shakespeare's mother's house is) and elsewhere. The result must have been somewhat of a trial to my father who had a keen ear for music and discord. Anyway he lost no time in getting money for an organ which was duly erected. Then the band with many expressions of gratitude was dismissed. All did except the bass viol who firmly refused to leave, stuck to his job and violed away in the gallery until death relieved him of his self-imposed duty. |

|

|

|

|

|

As boys we all sang in the choir and so far as I remember we all enjoyed doing so. On a certain Sunday afternoon just before service two of us climbed up through the belfry on to the top of the tower for the purpose of cutting our initials on the lead-covered roof. Fred kept cave whilst I worked away at the job on hand. Presently Fred whistled a warning, having spotted the Guvnor in cap and gown, coming through the churchyard gate, and hurried down without delay leaving me to shut the trapdoor. It was important that the Guvnor should not be aware of the fact of our escapade as it was against orders and the consequences entailed were easy to predict. Realising the necessity for speed it was a matter of split seconds I bundled down past the bell loft and reaching the next platform made a jump for the vertical ladder which led down to the vestry. Missing the top rung I fell about 20 feet landing on top of the assembled choir, rebounding on to a wooden bench and thence to the stone floor, this at the precise moment of the Guvnor's arrival. I was carried down to the Vicarage for rest and repairs whilst the boy who had broken my fall was excused from attending service. |

|

|

Upon being examined by a chiropractor, fifty years later, he remarked that I had a pronounced curvature of the spine rather like (and not inappropriately) a note of interrogation, for at what point of my career it had occurred must remain a mystery, probably however the above incident may have been responsible. It does not matter now anyway. |

|

|

|

|

|

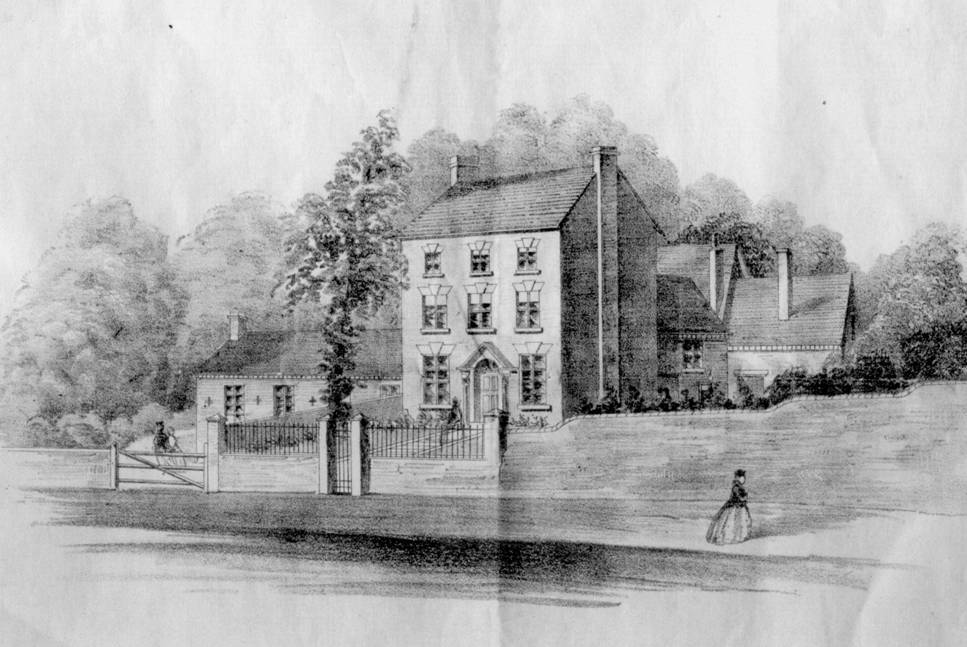

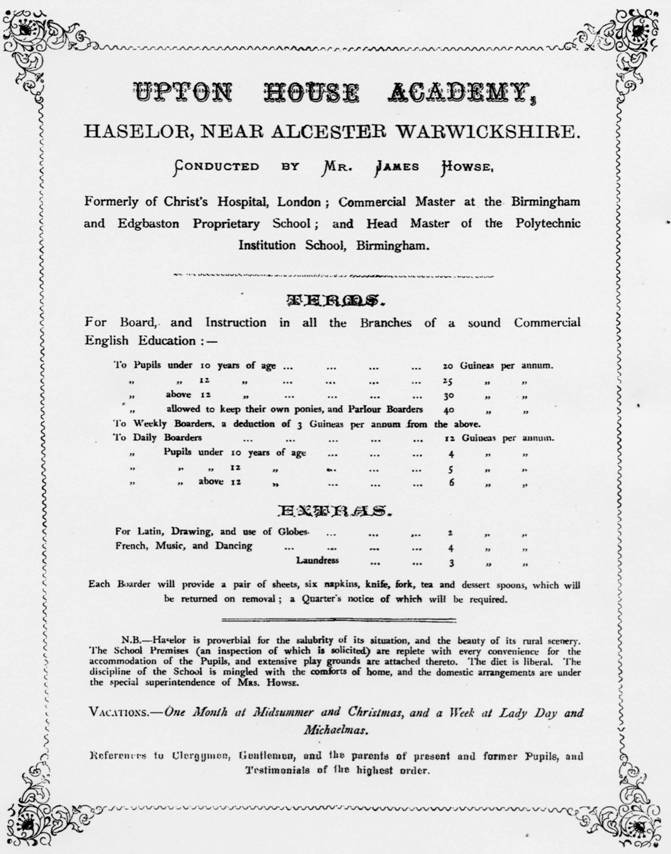

Upton House Academy |

|

|

Haselor, at the time, possessed a "Young Gentlemen's Academy", a grandiloquent label for what was really a school for tradesmen's sons, whom the proprietor, "Old Howse", polished up by putting them through the higher courses in calligraphy and book-keeping. My father, who had removed me from Woodcote House, where such accomplishments would have been regarded as infra dig, handed me over to this practical tutor to correct my glaring deficiencies and thanks to him I formed the habit of expression myself legibly whilst my arithmetic has always been above the (Sykes) average. |

|

|

The Upton Academy Brochure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When we were all growing up in the seventies and eighties the family income was under £300 a year, but my dear mother was such a wonderful manager that somehow or other it was made to go round. Wages in those days were on a fairly low scale. In her diary for 1863 I found this entry: "Engaged Elizabeth as cook at £6 per year." It must have been satisfactory to both as she remained for 15 years. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

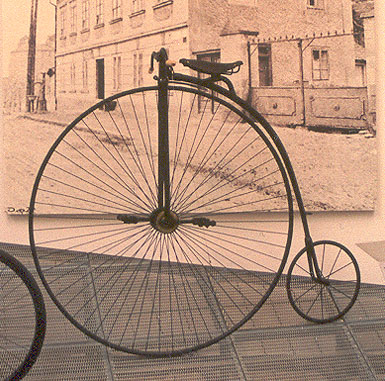

This type of bicycle was invented in the 1860s in France, and first manufactured by the Michaux company from 1867 to 1869 the time of the first bicycle craze, and copied by many others during that time. It fell out of favour after the summer of 1869, and was replaced in 1870 with the type of bicycle called "ordinary", "high-wheel", or "penny-farthing". |

|

|

|

|

|

Vehicles for transport consisted of a pony-carriage and two "bone-shakers". The latter were wooden wheel bicycles shod with iron tyres. I suppose there are not many today who learnt to ride on these fearsome contraptions. Then came the "spider" with a 56in wheel in front, a curved backbone and a little wheel behind. One reached the saddle by means of two steps. There was a spoon brake over the front wheel which, if applied too suddenly, caused the thing to somersault and there you were! Coasting down the hills with legs over the handlebars was always rather thrilling as a speed of 50 miles an hour was often attained. To touch the brake would have been fatal, once started it was literally "neck or nothing". "You boys will be brought home on a hurdle one of these days" the Guvnor would remark cheerfully; then, as an afterthought, "However nought never comes to harm". |

|

|

|

|

|

The Spider or later to be known as the Penny-Farthing. |

|

|

Cottage women in Alcester streets used to hoot execrations as we rode by, daring us to run over their brats, quite blind to the fact that the cyclist would probably suffer far more than the infantile victim already on the ground. |

|

|

These high bicycles gave one a commanding view of the country and I doubt if ever in afterlife I enjoyed anything so much as a long spin through the leafy lanes of Warwickshire in summer-time. |

|

|

On one occasion I rode from Weston-super-Mare to Haselor, just on 100 miles in one day. It was nearly midnight when I arrived home owing to the fact that I had wasted precious time en route by descending a coal mine near Clifton and watching a military review in progress at Bristol. |

|

|

|

|

|

Kinwarton Church & Rectory |

|

|

At the age of 19 I began to feel a bit desperate as to the future of a rather "not wanted" youth. Living in the next parish was another parson's son, a great pal of mine. We compared notes and came to the conclusion after many discussions that the sooner we set off to seek our fortunes the better. He had an uncle in Queensland. Why not write to him and say we were coming out? Good idea! He wrote. Then the news had to be broken to our respective fathers. The reception of the glad tidings of our resolve was typical of the manner in which parents of those days viewed these things. After leaving my pal at Kinwarton Rectory I cycled home, burst into the drawing-room where my parents were sleepily reading prior to going to bed. "M. and I" I remarked "have decided to go to Australia." My father, with a look which he might have reserved for the village idiot, said quite gently, "Tell us all about it tomorrow old boy good night". |

|

|

"M" is short for Malcolm, eldest son of the Rev. Henry Purton, Rector at Kinwarton 1877 - 1909. |

|

|

All things come to an end and my father decided I had better read for the church. So home I went. The History of the Prayer Book, Paley's Evidences and Greek Testament were all assailed in their turn. I started a Sunday School which the Guvnor thought "might be a good thing" marshalled the scholars each Sunday and led them to church and finally was taken to Lichfield College to interview the Principal. |

|

|

On the way home the Guvnor confided to me that the fees would cripple his resources unduly and in short it was out of the question. So a possible bishop was turned down. And "what next?" seemed to be the problem which must at once be taken in hand. |

|

|

On my first Sunday at home, after being absent in Australia for 9 years, I walked over the fields with him to morning service at Billesley. He had pocketed a sermon haphazard before leaving. Imagine my feelings when the "Return of the Prodigal" turned out to be the subject chosen for the day! I have often wondered since if it was intentional, or just a bad shot. |

|

|

Haselor, within three miles of the ancient town of Alcester and six of Stratford-on-Avon, where we were privileged to spend our younger days, is a typical village of "leafy Warwickshire". On gently undulating land, flanked by wooded hills set well back from the main highway and watered by the River Alne. It was a gracious example of rural England. An indelible picture on the mind when roaming over the faraway lands beyond the sea. I write sadly in the past tense, since Birmingham only twenty-five miles distant has, octopus-like, been spreading out her tentacles and despoiling the fair landscape of much of its pristine charm. |

|

|

|

|

|

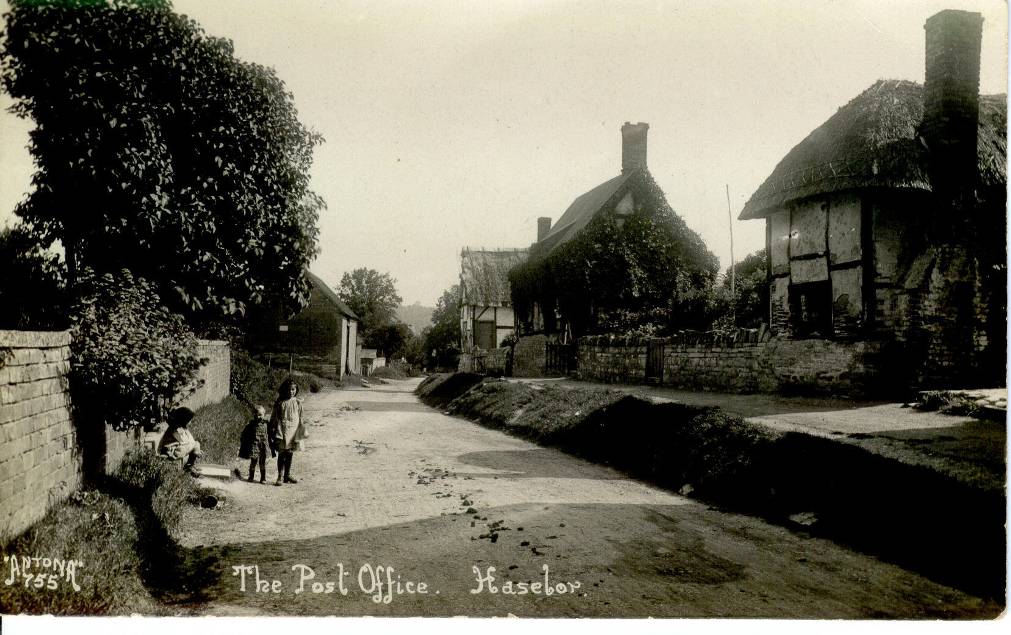

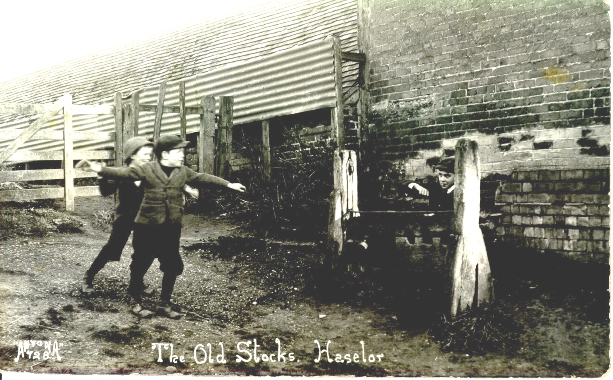

With its intimate village street rambling over the hill, its thatched and gabled cottages, the old stocks in convenient proximity to the village pub, its Church with Saxon tower set aloof in quiet dignity, on a green hill between it and the hamlet of Walcote, Haselor had a charm of its own which must always live in the memories of those who came beneath its spell. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A farmer's son, Percy Tunnicliffe Cowley, expresses something of the spirit of the place in a few touching lines which I am glad to have saved from oblivion. Here they are. |

|

|

HASELOR |

|

|

That's where I played in childhood's happy days |

|

|

In country lanes with country children's ways, |

|

|

And now |

|

|

Asleep together in the grave they lie. |

|

|

The sun is sinking blood red in the west, |

|

|

The birds are singing day's sweet lullaby |

|

|

While father and mother are at rest! |

|

|

There in old Haselor churchyard on the hill |

|

|

Away from busy life all calm and still |

|

|

They lie asleep. |

|

|

Farewell old home, so careful and so kind, |

|

|

Why should we sorrow, we who're left behind? |

|

|

Why should we weep? |

The grave of William Tunnicliffe Cowley and his wife Rosa Matilda in Haselor Churchyard. |

|

For soon we too shall seek our rest |

|

|

And sleep! |

|

|

|

|

|

On the edge of Walcote is the ivy-clad Vicarage, my parents' home for forty seven years, whither we returned like homing pigeons from our many wanderings about the world. That it was built at the base rather than on the flank of Church Hill with a commanding view over the surrounding country was apparently due to the fact that the site had been given for the purpose by a Canon Seymour, a close friend of my father. Perhaps other land was not available, perhaps it was to be that the fine old church should always retain its splendid isolation. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Cider Mill, c1920, and up the road a derelict farmhouse and pub, known as the Paul Pry Inn. |

|

|

Up Walcote Street was, and may be still is, an ancient cider-mill said to date back five hundred years. Here an old white horse with bandaged eyes plodded round and round, causing a huge millstone to revolve in a circular stone trough wherein the juice of apples and pears was expressed. This one-horse power marvel enthralled us as children and a sip of sweet cider from a horn mug added to the attraction. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Paul Pry Cottage in the foreground and Paul Pry Inn behind. The garage to Paul Pry Cottage stands on the site of the Inn. |

|

| (Note: Cows walking up the road to farm buildings, which is now "Flaxhide". These cows have come from fields, on the Haselor side of Walcote. Also note: There is a thatched corn rick in the garden of Walcote Farm.) | |

|

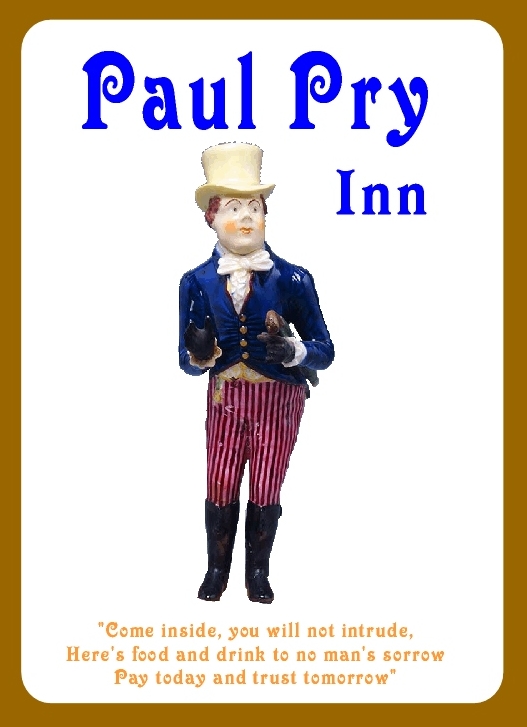

There had been, years before our time, a pub on a siding above the road. It bore on its sign a white-hatted Duke of Wellington with the following invitation: |

|

|

"Come inside, you will not intrude, Here's food and drink to no man's sorrow Pay today and trust tomorrow." |

|

|

The writer, as a young boy saw an old inn sign what he thought looked like the Duke of Wellington. The facts are that it would have been Paul Pry that was on the inn sign. So from this article, I have been able to reproduce the Paul Pry Inn sign. |

|

|

|

John Liston was the leading comic actor of the first half of the 19th century. In 1825, with 20 years of experience behind him, he created his masterpiece character, Paul Pry, in John Poole's farce of the same name. Pry is a man consumed with curiosity, an interfering busybody unable to mind his own business. With his striped trousers, hessian boots, tail coat and top hat, Liston moulded Pry into a uniquely endearing character. Most memorable was the umbrella that Pry conveniently left behind everywhere he went so that he would have an excuse to return and eavesdrop.

The public became totally infatuated with Liston and Pry. Images of Liston as Pry appeared on inn signs, in print shops, in the pottery warehouses, on pocket handkerchiefs, stamped on butter, adorning snuff boxes and in toyshops. The Staffordshire, Rockingham, Derby and Worcestershire porcelain factories all produced figures of Paul Pry. It was such a hit that Paul Pry was still being revived in the 1890s with Liston's performance imitated, costume and all.

|

|

|

|

|

Bentley beagles with Squire Maude Cheape at The Crown Inn, Haselor. |

|

|

The Crown Hotel at Haselor, since the old Duke was but a memory and had long ceased to invite customers inside, was the rendezvous for the old white-smocked gaffers with blue worsted stockings who, to escape the clattering of their females, forgathered within the bar parlour, lit their churchwarden clay pipes, filled with "black shag" tobacco, and settled the affairs of the nation to their own best approval and satisfaction. Seated on the oaken settles with high backs to keep the wind away, they called for their "moogs" of ale and with an air of "I will take mine ease in mine inn" derived such comfort and social converse as the place afforded. Very alluring and satisfactory, tinged with a spice of danger as to what the old woman would have to say about it later the motto of the Crown was "ad aethera virtus". |

|

|

|

|

|

Anthony Knight, the owner of the cider-mill, on one occasion had wandered over Church Hill and taken part in a pigeon-shooting competition at the back of the Crown. Returning home through the churchyard in the small hours, as he rounded the east end of the church, he saw a ghost with arms outspread apparently holding him up. With ready wit he slipped a couple of cartridges into the gun he was carrying, fired both barrels at the apparition and making a detour arrived home shaken but safely. The following morning disclosed the fact that Anthony had well and truly peppered a white marble cross which had been erected near the pathway. Sad to relate that the relict of the deceased demanded and obtained damages for the outrage! |

|

|

|

|

|

The Great Alne Railway Station, with the station master and his wife. Picture supplied by John Earle. |

|

|

|

|

|

This picture, Great Alne Station c1889, is the same period in time as the writer of "Haselor Memories". |

|

|

Picture supplied by John Earle |

|

|

As it were yesterday I can recall our departure from the little railway station, Great Alne, which as years went on was to be the scene of so many leave-takings and home-comings. M. with only a few minutes to spare strolling casually along the line gun over shoulder, as if he were off on a day's rabbit-shooting. The assembled families on the platform. My parents accompanied us to town. |

|

|

In looking over his accumulated stock, after his death, I came across one sermon written for King Edward's coronation, and found that it had done double duty, for, on the accession of King George to the throne, it had been adapted to the occasion by the simple process of changing names! He no doubt would have referred to it as "tricks of the trade". |

|

|

|

|

| This photograph shows the wreaths after the funeral of Rev. John Heath Sykes who was buried to the right of the the gravestone in 1912. The gravestone is that of his son, Hugh Percival Sykes who died in 1896. | |

|

|

|

| This photograph shows the newly erected gravestone, of Rev. John Heath Sykes and the sundial. The sundial reads:- Erected March 21st 1914, by the Parishioners of Haselor, in affectionate remembrance of the Revd John Heath Sykes, who was the Faithfull (sic) Vicar of this Parish for 45 years. 1867 : 1912. | |

|

|

|

|

The writer of "Haselor Memories", Francis William Sykes, with his wife and their 7 children, taken at their house in Hemyock, Devon, shortly before they emigrated to New Zealand in 1920. |

|